Chapter 2, The IRT Subway

They Moved The Millions · by Ed Davis, Sr.

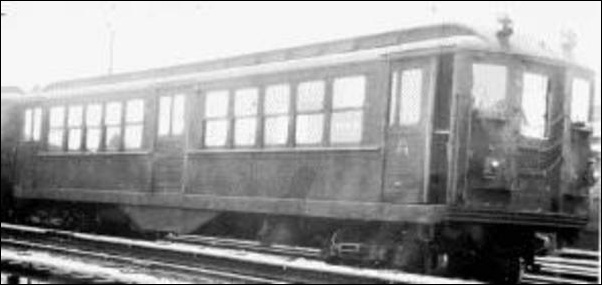

The composites as built. Much of the equipment needed for service has yet to be installed. In the early days rapid transit coaches hadn't developed much of their distinct styling, looking like conventional railroad cars. IRT Co.

The IRT, or Interborough Rapid Transit Company, was the operator of the city's first subway system, which was built by the city and operated under contract. As we have already read the Interborough also took over ownership and operation of the Manhattan elevated lines about the time the subway was opened for service. The IRT had one basic style for rolling stock; even though there were some variations of design the IRT departed little from the basic railroad coach appearance for over 20 years. Unfortunately the Interborough system as originally built had close clearances built for the approximate dimensions of the coaches of the elevated lines which hadn't changed since the 1880's, whereas standard railroad coaches were getting larger. The basic IRT body dimensions which even the newest cars in these modern times have been built to were thus: 51 feet long, 9 feet wide, and about 12 feet high from the top of the rails to the top of the roof.

The IRT equipment had always implied ruggedness and reliability and its many years of faithful service proved it so. It offered itself strongly for the affections of the railroad buff and in turn received much nostalgic attention.

Section A: The Composites

Before the subway was opened for service in 1904 there had been a few years of planning for the rolling stock which was to be used in the subway. They were of course to be electrically powered and have automatic air brake. An all-steel car was the most desirable type of car not only for greater safety in case of collision but mostly for a fireproof body for this underground, passenger hauling railway. At this time however wood was the industry standard for carbody construction and the car building industry already had a backlog of orders for wooden cars and did not care to experiment with steel body construction.

This view of a composite under construction shows framing used in construction of wooden cars. IRT Co.

The solution was a "protected" wooden car which was a lot like the coaches of the Manhattan elevateds. These "protected" cars had the same seating arrangements and similar interiors but were built with vestibuled ends rather than open platforms which was already a dated practice but was still being used on the els. The "protection" was a skin of copper over the wooden construction, and the fact that these cars had metal in their construction gave them the name "composite" cars over the years.

Sliding entry and exit doors were used on these setting the standard for all future subway car construction in New York except of course for door locations. These were manually operated by a system of levers; until 1915 this was to be the only type of door control on the IRT subway. As with the gate cars on the els they had the same problem of high crew costs needing so many trainmen to operate the doors, but for their time it was a good idea. As late as 1958 there were still some IRT subway cars in service with this arrangement.

Handsome interior of the composites when they were new. Similarity between these and the elevated cars is apparent. When center doors were installed the cross seats were removed. Only longitudinal seating was used which has become standard IRT car arrangement in all succesive rolling stock. IRT Co.

These cars were powered by two traction motors on the motor truck with the other truck being a trailing truck, also a standard practice for all IRT motor cars, subway and elevated. They would develop 400 horsepower per car and with the gearing and control system used would propel a train at 45 miles per hour. Most of these cars, and most of all IRT rolling stock was powered, or motor cars, but some trailer cars were included in each train. These were of the same construction as the motor cars but lacked motors and controls. If necessary trailer cars could be converted to motors. For the years of ten car train operation there would be seven motors and three trailers, shorter trains would of course have fewer trailers.

Control systems on these cars were high-voltage with manual acceleration, that is when accelerating a train from a stop the motorman would notch up the controller one point at a time; these cars and all New York subway equipment to date (with the possible exception of some experimentals) made transition from series to parallel after the train's load was gotten underway, a speed of roughly 18 miles per hour on subway equipment under most circumstances. In the case of equipment on the New York system the transition point was on the master controller which the motorman operated so there were no additional controls to be switched over to make transition. A dead man feature was included on these controllers which would apply brakes in emergency by allowing complete exhaust of the brake pipe if the controller were let go for any reason including death or sickness of the motorman. This has also been the practice on all passenger equipment of the New York city subways and els until the present time.

After only some few years of service it was found that excessive dwell time in stations was being taken up for loading and unloading of passengers in the subway, and it was decided that a door at each end of the car was not sufficient to handle the crowds of people that were riding the trains. A center door was added to these cars to expedite the movement of passengers and the center seats were removed; from this time on IRT subway cars would have only longitudinal seating; the last cars for the IRT subway to be built without a center door were built in 1907; soon all cars lacking same were to have them installed. Along with the addition of the center door a steel fishbelly girder was added to each side of these cars to compensate for structural strength lost when the car sides were cut for that door. None of these cars were converted to Multiple Unit Door Control as were some of the Manhattan el cars and all-steel IRT subway cars which were built with manually operated doors.

The composites had a brief subway career; it was found that they were not that well "protected" from fire for service in the subway and with the delivery of the 1916 fleet of all-steel coaches they were transferred to the Manhattan (elevated) Division. They were outlawed from the subway by order of the Public Service Commission. They served on the els for approximately another quarter century, but in no case to replace the MUDC cars which we have read about, which would long outlive these composites.

The "Composites" ended their days in service on the shuttle from 167th St.-Jerome to the Polo Grounds, on the last surviving part of the old 9th Ave. el. These cars were a 50-50 mixup of subway and elevated car equipment and bore only vague similarity to their original appearance. Robert C. Marcus.

When the composites were transferred to the els they were found to be overweight for the structures which were not built for heavy equipment. The Interborough fabricated in its own shops replacement trucks for these cars were were light in weight and quite flimsy in appearance. (If you remember the story of the "Q" cars you will see that they lasted many years.) Weight was better distributed by using the maximum traction arrangement with one motor and one trailing axle on each truck, which would result in having a motor at each end of the car. The trailing axle wheels were somewhat smaller, 32" as motor axle wheels were 34". This was allegedly for better traction. Also, lighter motors of considerably less power were installed at this time.

Shortly after the composites were retired these lightweight trucks were installed on the BMT "Q" cars as we have read, and these home made Interborough trucks were in service on the "Q"s until 1969. The composites finished out their days on the Manhattan elevated; none have been preserved.

Section B: The First Steel Cars

Almost a half-century old, High-V 3808 (Standard Steel, 1910) is still handsome in this yard photograph. While quite small, the IRT coaches were impressive. The sizes of the trucks are markedly different; the truck to the left is the motor truck, to the right is the trailing one. Victor Rucklin collection.

While the composite cars were being planned and built as a second choice for the original subway the Interborough still hadn't given up on the idea of a steel car. If the Interborough, and eventually the entire subway, could be considered at the most a short line railroad (purists don't consider the subway a railroad but by all physical aspects it is) this meager line of less than 100 miles was to become a pioneer planner. When rapid transit lines were profitable their revenues were way greater per mile than the most profitable steam common carrier line, the Pennsylvania.

Those who study railroads are well aware of the engineering abilities of the mighty Pennsylvania Railroad, which probably engineered and built some of the most powerful and efficient steam locomotives in the world for their time, not to mention eventually planning and building the most classic electric locomotive of all time, the mighty GG-1. The Interborough, along with the Pennsylvania Railroad and the cooperation of George Gibbs of the Pennsylvania, was able to help produce the first steel passenger car built in the United States, at the Altoona plant of the Pennsylvania. If not locomotives, why not steel coaches too? This was not a production model car, just an experiment that proved steel passenger cars to be practical, and of course within a few years wooden car construction would become obsolete.

By 1904 the American Car and Foundry Company at Berwick, Pennsylvania had started to build steel coaches for the Interborough and about the same time was building similar coaches for the Long Island Railroad which were to be the MP-41 class, identical in body but with appliances for surface railroad service rather than subway service. Not to get off our track here, let us stay with the IRT; but those Long Island cars were electric multiple unit also, and not steam-hauled. American Car and Foundry was to build 300 of these cars for the IRT which in their original appearance were very much Pennsylvania Railroad, and which were to be known as Gibbs cars to rail buffs throughout their career (but to operating personnel were known as Merry Widows, which had a vulgar implication owing to their totally enclosed vestibule areas.)

The Gibbs car when new. In this builders photo the trucks shown were not the ones used in service. Motor trucks were larger than the trailing ones and, in fact, both were heavier than the ones shown here. Center doors and fishbelly girders would be installed a few year later. IRT Co.

In 1904 and 1905, while the subway had already been opened for service with the composite cars built immediately prior to its opening, these all steel Gibbs cars were delivered. They, like the composites, were built without center doors. Side vestibule doors at the ends were manually operated; seating was the same style as used on the elevateds. These cars also had high voltage controls and automatic air brake, further mention of this until others features were added to rolling stock will be superfluous. Standard IRT motive power practice was now established; two motors of 200 horsepower each were mounted on one truck (number two) and the other truck (number one) would be a trailer. Only the Steinways and World's Fair cars would have less horsepower.

These cars had the most attractive interiors of all IRT coaches, while not really ornate they had some metal interior trim which subsequent orders lacked. Windows were to be opened from the top rather than the bottom which was to become practice for all New York subway cars. Windows were in sets of three at each end with the remainder paired, another feature which was not to be repeated on IRT subway coaches. This was Pennsylvania Railroad styling.

This end view shows the handsome rugged construction of the Gibbs cars. Link and pin couplers and standard railroad air hose connections would later be replaced with type "J" traction car couplers which allowed air couplings to be made thru the coupler. Corrugated steel "anticlimbers" had not yet been invented. IRT Co.

While initially successful the same problem of insufficient door space for quick entry and exit of crowds, which plagued the composites, also plagued these Gibbs cars. Center doors were to be added to these cars also, center seats were removed, and fishbelly girders added under the center doors to strengthen the body as cutting doorways in the sides weakened the bodies.

Many other modifications were made to these cars over the years. Electric braking, which we will later explain was added to them to make them compatible with equipment delivered in 1910 and 1911. Motorman's indication, which indicated that all train doors were closed and locked and was the motorman's signal to start the train at stops along the line, was also added. About half of these cars were converted to Multiple Unit Door Control during the early twenties along with other subway stock and as we have mentioned, the els. At this time the converted cars received steel doors in place of their original wooden ones, and sliding end or storm doors rather than swinging doors.

The sliding vestibule doors inside the cars were never removed from them and until they were retired from service the motorman still had the entire vestibule to himself rather than about one-third of it which would become standard IRT practice. This was to the bane of the "junior motormen" which we have read about; passengers could not look out the front door window when one of these cars was on the head end, and in fact the entire vestibule area on front and rear cars, if one of these cars was in that position in the train, was closed to passengers.

The Gibbs cars were the heaviest cars ever used in IRT service. As many features were added the weight mounted; the weight of an MUDC Gibbs car was 89,450 lbs., nearly 45 tons. To show how heavy and solid these cars were, a modern, 85 foot long, multiple unit commuter car for the Long Island Railroad with air conditioning weighs in only slightly heavier. The Gibbs cars were only 51 feet long and had much less machinery. The average weight of most IRT motor cars with MUDC was about 39 or 40 tons; these would have similar machinery as the Gibbs cars.

The Gibbs cars served the IRT and later the municipal operators for some 53 years. They were very much in evidence on the Lexington-Pelham locals, the West Side Locals, and the Broadway-7th Avenue express. As new equipment was introduced on these lines they were retired, their very last service was on the 7th Ave. locals from South Ferry to Harlem. As old as they were their standard railroad coach appearance externally did not make them appear strange as nearly two thousand coaches of somewhat similar design were still in service on the IRT.

|

First steel passenger car ever built. 3342 poses later in life, apparently used as a revenue collection car. Victor Rucklin collection. |

A Gibbs car with center door added, but it's still a "battleship" with manually operated end doors. Second car is a Gibbs MUDC; this was probably on the Pelham Bay line. Note the narrow windows by the center door. The big fishbelly girder was to replace support for the "box girder" carbody as the center door weakened the framing. Victor Rucklin collection. |

|

This is how the Gibbs cars looked after their final conversion. New steel end doors were installed when MUDC was installed in the 1920's. New sliding end doors with windows were installed also. This view is at 125 St. and Broadway, a southbound train. Victor Rucklin collection. |

Just before the new cars showed up on the Pelham Bay Line, Gibbs "battleship" No. 3400 leads a train standing by for service. June, 1955. Photo by Joseph Frank. Collection of Ed Davis/Peter Horowitz. |

One car, 3352 has been saved from this fleet and has been converted to its original Pennsylvania Railroad appearance at the Seashore Trolley Museum in Maine. It would have been better left as it was retired with the IRT conversions as it served about 47 years in this style.

Let us not forget how this short line rapid transit railroad teamed up with the great "Standard Railroad of the World", the Pennsylvania, (which built everything differently from other railroads and was not so standard after all) to revolutionize the future of passenger car construction when no established car builders of the day wanted to at least try! The lesson soon rubbed off.

Section C: The Deckroofs

In 1907 the IRT was to get another order of 50 all steel cars, all of them motor cars, to add to their fleet. The design of these was to be markedly different from that of the Gibbs cars. Windows were to be evenly spaced. The roof design was to be a clerestory roof but not the standard railroad roof design with tapered ends. The roofs were copied from a popular trolley car roof design of the time, a deckroof. On this type roof the clerestory section ended abruptly at the vestibules before the ends of the car. The side doors at the ends of these cars were to be considerably larger than those on the merry widows, or Gibbs cars, in an attempt to speed passenger loading.

Deckroof 3655 brings up the rear of a Broadway-7th Ave. Express at 238th and Broadway in the mid '50s. The deck roof gave these cars a markedly different appearance from the rest of the IRT stock. Operating levers for the doors on these "battleships" are visible at each side of the end door. Franklin B. Roberts.

The change that would become the major innovation to be used on future orders for the IRT was the elimination of the sliding doors that totally enclosed the end vestibules. On this and all subsequent orders of cars for the Interborough the vestibule area would be available for standing passengers. To make space for a motorman's cab there would be a pair of swinging doors that would open from opposing bulkheads on the right hand side of each vestibule, which could be opened and fastened in position to make an enclosed cab area on the vestibule at the head end of the head car. A motorman's cab was then created, to be eliminated by simply swinging the doors shut against the bulkheads when this area was not at the head end. One door was to cover the controls and brake valve and the other would cover the folded up motorman's seat, and again the area would be available for passengers and for use of the side door at that location.

Deckroof 3662 being restored at the Branford Trolley Museum near New Haven, Connecticut. The deckroofs were the only old IRT stock without fishbelly support girders under the center door.

There was no other change in these cars that rates mention; they were mechanically the same as their predecessors, interiors were somewhat plainer but seating remained the same. A few years after their construction these cars also received the center doors but no fishbelly girders; they were the only cars of the Interborough fleet built through 1925 that did not receive this feature with center doors.

The body design after remodelling and with the exception of the deckroof was very much similar to what would become the standard IRT body. The deckroof design was never repeated on subsequent orders of IRT cars.

These cars served until 1957 on the Broadway-7th Ave. Express line and the 7th Ave. Local lines of the IRT. One car, number 3662, has been preserved at Branford Trolley Museum in Connecticut.

Hi-V 3963.

Section D: A Standard Body Design

Rolling stock for the Interborough had thru 1907 been delivered in three different styles, but a standard body design was to evolve and endure for some 16 years and number a total of 1,953 units. In 1910 and 1911 a total of 325 cars were built to this standard design; they were manufactured by American Car and Foundry, Standard Steel Car Company, and the Pressed Steel Car Company.

These cars shared some of the features of the 1907 Deckroofs, notably the large side doors and window arrangement. They reverted, fortunately, to conventional railroad roof design, and introduced several new features. These cars were the first to be delivered with center doors which had proven their necessity for faster loading and unloading of passengers. The vestibule doors on these cars were still manually operated, center doors were pneumatically powered. There was more steel used in construction of these cars; where prior orders had wooden doors these had steel doors. All cars of this order were motor cars.

Since these cars had center doors when built the seating pattern employed was all longitudinal seating, the first deviation from the prior arrangement with cross seats at the center of the cars. This seating arrangement would be used on all future orders of cars for the IRT.

Electro-pneumatic braking was introduced about this time, using a basic automatic air brake system with "R" type triple valve. What has become known as electric braking is not to be confused with dynamic brake which temporarily converts traction motors into generators to slow a train down. Electric braking is a supplementary system which, by means of braking circuits thru the train operates control valves simultaneously in each car rather than the serial action which takes place when air is exhausted from the brake pipe thru the train, at the motorman's or engineer's brake valve. When air is set with electric braking each car reacts at the same time and a much quicker and uniform brake application results, such as would occur if there were a motorman operating a brake valve in each car. Easier train handling and faster running times were the result. Should the electric feature fail a train could simply be brought to a stop using the automatic system which was in fact on the same brake valve.

|

Car 3878 leads a southbound train of High-V's at 238th St. and Broadway. The old Irish motorman is undoubtedly an old IRT veteran as is his train. Franklin B. Roberts. |

High-V 3859 in the center of a train at Dyckman Street. These faithful old relics were soon to be retired. Franklin B. Roberts. |

The ME-21 brake valve was used on these cars and all previously constructed steel cars had this feature installed. The braking system was known as AMRE, simply the manufacturer's schedule for various brake systems.

Other features of these cars had already been used on earlier orders: Motive power and high voltage control systems remained the same. The fold away cab design remained and would remain on all IRT car orders thru 1925. The body style, which was only a revamping of traditional railroad coach styles, was indeed a handsome and rugged style, and was apparently quite satisfactory for the service as the IRT kept this design so long. In fact, it was very much in evidence until 1964 when the last of the old IRT stock was retired from mainline passenger service.

During the early 1920's when the IRT was converting much of its fleet to multiple unit door control all but 59 of these cars received this conversion. Appearance was changed little, only the levers which had previously been used to open and close doors were removed, and rubber shoes were installed on the doors for safety. By this time the use of motorman's indication had become standard; rather than trainmen and the conductor passing proceed signals by bell thru the train to the motorman when doors were closed, a signal light would light in the motorman's cab when all doors were closed and locked. This would be the motorman's "Proceed" signal at station stops along the run. The MUDC feature and indication, or starting signal, improved running times and reduced manpower requirements at the same time.

These standard body high voltage cars were used in service on the IRT West side locals and Broadway-7th Ave. Express lines as late as 1959; only a few years before the entire fleet was still in service. A few were used in work service as late as 1960. None of these cars have been preserved in museums.

While the high voltage control system was a rather primitive system it was nonetheless rugged and reliable. Long after their demise the "High-V's" were remembered by "old-timers" for their tremendous pulling power and ability to make running time, even if the presence of 600 volts in the controllers in the motorman's cab was hazardous.

|

March 1952 - a "battleship" standard body High-V at 155th St.-8th Ave., last remaining station of the old 9th Ave. El. Swing bridge in the background used to belong to the New York Central, later bought by the IRT to connect the el to the Jerome Ave. line in the Bronx. All of this is now gone. Collection of Peter Horowitz. |

Retired passenger equipment often served in work service for some time before eventual scrapping. Here is Flivver 4126 at 239th St. yard in the early 1960's, Note the Van Dorn link and pin coupler for use with antiquated work cars, and the single brake pipe hose hanging in place of the original draft gear with air couplings in the coupler head. Victor Rucklin collection. |

Section E: The Flivvers

Following construction of the standard body High-V's there was a lull of four years between deliveries of new cars for the Interborough. In 1915 some 500 new cars were delivered, built to the pattern of the 1910 High-V's. The only exception to the styling of the 1910 cars was on the side and end doors, which were less ornate. Where the 1910 cars had three panels under the side door windows, the 1915 cars and the remainder of the fleet to follow had one large panel.

There were three different car types built in 1915. There were the 12 Steinway types built by Pressed Steel; we will read about these later. There were also standard motors and standard trailers. As there has been some disagreement among sources of information on this matter we will discuss the "Flivvers" as they were toward the end of their careers rather than when new and then go back to their origins. Of the 1915 order from Pullman there were 124 motor cars and 354 trailer cars. Of the trailer cars, 54 of them were mated with the motor cars of this order for most of their careers and these cars, both motor and trailer, were known as "Flivvers."

Braking equipment on the "Flivvers" was AMRE with ME21 brake valve as on the High-V's. These were the last cars to be equipped with this schedule air brake.

The Flivvers had low-voltage control but were never called Low-V's by operating men as they were different from the fleet of cars which were called the Low-V's. Veteran IRT railroaders had said that the "Flivvers" were built as high-voltage cars and converted later, to low voltage. It has been said by others that the "Flivvers" were built as low-voltage, as a transition cars between the High-V's and Low-V's but sharing some characteristics of each. Either story could be true as there was low-voltge control equipment on other systems before 1915 and it is likely that the "Flivvers" were low voltage when new. However other facts back up the IRT men's story. For one thing the "Flivvers" had the same big brass controller handles in motormen's cabs that older high-voltage cars had. There were the 12 Steinways delivered in 1915 also that were low voltage and had the plainer controllers as used on standard Low-V's. Furthermore with the IRT being as conservative as it was it is likely that the low-voltage Steinways were built as experimentals and that the company elected to continue ordering high-voltage equipment which in this case later became the Flivvers. Last but not least, as there was such a large order of trailer cars built with this group of cars, 300 of them being for the High-V fleet, isn't it likely that the entire order was delivered as high voltage? This is a long dissertation on this matter but hopefully a long standing difference of opinion can be settled by it. Since, to the IRT, the older system was already proven it seems likely they would have stuck with it and then when the Steinways proved satisfactory all new equipment from 1916 was on low voltage.

The 1915 cars were delivered with pneumatically powered, electrically controlled doors which was an innovation for the IRT, nevertheless they were built for service trained with older cars.

The "Flivvers" eventually were all MUDC cars. Although they were limited in number they were still a long lived piece of equipment. As the braking system was not compatible with the Low-V system (electrically it wasn't; pneumatically they were, as was all old IRT equipment) and the control system was not compatible with the High-V's, they were run in passenger service as solid trains of "Flivvers". They served until 1960 in passenger service on the Lexington Ave. expresses and the 7th Ave.-Bronx Park (East 180 St.) express. They also served as work motors for a brief time thereafter.

How these cars came to be known as Flivvers is unknown to the author. The only other usage of this word was in reference to old automobiles a few decades ago, and the term is seldom heard these days. While the name most likely implied a junky auto when it was popular the Flivver cars on the IRT were not in that category. They were good performers until their demise; none have been preserved, but then they were identical in appearance and sound to the Low-V's.

|

Flivver 4111, a 1915 Pullman product. leads a southbound Lexington Ave. Express in the subway at 149th St.-Grand Concourse about 1960. This train had ten motor cars, no trailers - an unusual makeup and would have outrun any of the newer equipment that would soon replace it. |

The autumn sun in late afternoon warms these Low-V's at Jackson Ave. in the Bronx in 1962. This classic scene would be changed forever in a few years. |

Section F: Low Voltage Cars, A Milestone

In 1916 another milepost was reached on the Interborough, the use of low-voltage controls on their rolling stock. While we have already mentioned that the Interborough was not a pioneer in the use of such controls, and in fact 12 low voltage "Steinway" cars were delivered to the IRT in 1915, this 1916 order was to set the standard for control systems for the Interborough and the entire rapid transit railway industry as well. Another milestone was reached with the delivery of these cars: Pursuant to an order of the Public Service Commission in 1916, the "Low-V's" would replace the Composite cars on Interborough Subway Lines. It was found that the "protected wooden cars", or Composites left a lot to be desired in both flammability and durability in collisions. They were transferred to the els as has already been read, replaced by all steel cars and from this point on the IRT was to have nothing but steel cars on their subway lines.

Very well on in years, Low-V 4974 (Pullman, 1917) is spotted for the photographer in a Bronx yard in the 1960's. Note the simplification of door trim as compared to the nearly identical 1909-11 model. Take a close look at the coupler-air hoses run into it for trainline connections. Note the electrical jumpers below coupler. This was the IRT's standard coupling apparatus. Victor Rucklin collection.

In appearance the first order built by the Pullman Company was identical to the Flivvers. The braking system was automatic, electro-pneumatic also, but a newer type. Brake valve was the ME23, which was an improvement as electric and pneumatic positions were at the same places. On the earlier ME21 there was an electric range and a pneumatic range and if the electric brake failed the motorman would have to move the handle to pneumatic service. On this brake valve, the ME23, if the electric feature failed air would already be exhausting from the brake pipe at the valve and a brake application was being set up. Perhaps time was not allowed in such instance to make a perfect stop but much time was saved over the older system. Air brake schedule for these cars was AMUE. Triple valves were replaced by "Universal" valves, in this case the UE-5, in which electric and pneumatic features were combined in one control valve. With the exception of some few BMT cars, this ME23 brake valve and AMUE system would be used entirely on the Interborough, Brooklyn-Manhattan, and Independent lines through 1940 for all new car construction. Additionally several "steam railroads" used this system on their electric commuter cars.

A train of Lov-V's heads north at 174th St. station, bound for the city line at 241st St. and White Plains Road in Lexington Ave. thru express service.

Now, about low-voltage control, as compared to the pioneer multiple unit control system, high voltage. With high voltage equipment 600 Volts DC was used not only for traction power but to feed the motorman's master controller which in turn fed trainline circuits for "notching up", or running thru the steps of acceleration and making the transition from series to parallel as the train was gaining speed. Of necessity 600 volts had to be run from car to car, and this was at times a hazardous situation. With low voltage control, voltage ranging from 32-40 Volts DC, supplied from batteries mounted on each car, was fed to the motorman's master controller. This in turn would be fed thru trainline circuits which would operate relays in controllers under each motor car and cause distribution of traction power to the motors. High voltage was removed from the motorman's cabs, and since it was not necessary to have a high-voltage bus line thru the train, should the train run into a power section where power had to be removed there was little risk of re-energizing the 3rd rail where power had to removed for some emergency. At one time the IRT had signals which would require a train to stop before crossing into a power section where power had been turned off, strictly for stopping the older type high-voltage equipment which would bridge the gap and cause a possible catastrophe.

New at the builders in 1925, Low-V 5618 still lacks much of the hardware it will need to go into service in the subway. Although a "J" type coupler with integral air pipes is mounted, a standard railroad brake pipe hose is visible, no doubt this was needed for movement around the plant. A member of the last order of Low-V cars, the 5618 would serve commuters until the early 1960's. The styling developed in 1909 is still apparent on this car. Compliments of Nate Gerstein.

Along with low-voltage control came automatic acceleration. Whereas in the high voltage system the motorman would notch up point by point and drop out banks of resistance which kept the motors from getting full power and burning out while starting a heavy load (and in the process making transition) the low voltage system did this semi-automatically. The high voltage system had 10 points of acceleration on the controller; the Low-V's (in New York subway service this is, some railroads had more) had three power positions. Switching, for brief moves of a few seconds, the controllers would remain in first point; series, for allowing acceleration but not making transition, for operation up to about 18 MPH, and parallel or multiple where all steps of acceleration would be run thru and the train would reach maximum speed of about 45 MPH. A series of controls, thru a limit switch which sensed electrical load, would drop out of the banks of resistance and allow transition while tonnage was gotten under way and full speed would be reached. While a motorman could with this system notch up thru the three points, under normal conditions it was only necessary for him to "wrap it around" into parallel and the controllers in each car would, as explained, go thru the steps of acceleration. If a motorman were to do this with high-voltage equipment the overload switches would drop out and cut power from the motors to prevent their burning out. All rapid transit and electric suburban rolling stock in our modern times is low-voltage control, (as are diesel locomotives, at 74 volts DC as compared to a mean 37 volts DC for electric cars).

A southbound train of Low-V's arrives at Mount Eden on the Jerome line in 1961.

In addition to low-voltage control, powered doors and multiple unit door control which would be used on the Low-V's and installed on older cars as well set industry standards which are still in use today.

The 1916 order from Pullman did not end the Low-V saga. In 1917 another order from Pullman was to supplement the fleet. These were nearly identical but had ceiling headlinings of composition material which covered the ribs of car framing which had been exposed on all IRT steel cars up to this time with the exception of the Gibbs cars. The car numbers which had formerly been painted on window glass were now printed on steel plates. On the 1917 order brass window sashes instead of wood were used. The 1916 order and 1917 orders both were delivered with motor and trail cars.

In 1922 an order of 100 Low-V trailers was delivered by Pullman; 75 of these cars had air compressors for the braking system. These were identical in style to the 1917 order except that wooden window sashes were again used. The final order of Low-V's was delivered by American Car and Foundry Company in 1924 and 1925, again using wooden window sashes. These were all motor cars. At this time there were well over 700 Low-V's in service.

A Low-V in the subway at 125th and Lexington, heading south. A fast express ride to Brooklyn Bridge was in store for some of its passengers.

Interspersed among orders for Low-V's were deliveries of trailer cars of three types and also orders and conversions for Steinway cars, we will study this in the next section. By the year 1925, with the last orders for cars of standard body design with low-voltage control, the entire saga of IRT passenger equipment had nearly been written. A 50 car order in 1938 was an epilogue but what would be the IRT for over 35 years to follow was entirely in evidence by 1925.

The Low-V's would be in service on virtually all IRT subway lines at one time or another during their mainline career which spanned some 48 years. They were used principally on the Lexington Ave. express services and the 7th Ave.-East 180th St.-Bronx Park expresses but appeared elsewhere also. Some even appeared on BMT shuttle services with extensions on their sides at floor level to fill wider platform gaps on the BMT. This was only for about a year, about 1960. Their last years of service were in 1963 on the Lexington-Jerome line and until spring of 1964 some were still in service on the 7th Ave.-Lenox express. A few Low-V trailers survived as late as 1970 in service on the 3rd Ave. Line; by this time the only motor cars left were in work service.

Interior of a 1916 vintage Low-V, built by Pullman. The rattan upholstery is covered by red plastic. With few changes, all cars built between 1910 (3700 series High-V's) and 1925 looked almost identical inside.

In addition to downgrading these cars to work motors for pulling work trains, some were converted to other type cars. There were a few that received two motor trucks and became 800 RP locomotives for work trains; rather than their previous 400 HP rating with two motors on one truck they now had four motors; also they had a second compressor installed so as to provide sufficient air for hauling freight cars in work trains.

Some Low-V's were converted to alcohol cars for spreading de-icing fluid (alcohol and diesel oil) on contact, or power rails during snow and ice storms so passenger trains could draw power. Others were used as "rider" cars for track crews to ride in to work sites on work trains. Still others were converted to collection cars for the collection of money from station agents on the system; these had a changeover valve which allowed them to be run with automatic air brake with old type equipment or straight air/emergency brake pipe with postwar cars as motive power. Incidentally, rider cars, alcohol cars, and collection cars had their traction motors removed and were run as trailers.

Although built identically to the 1909 design the Low-V's built from 1917 to 1925 appeared a bit different inside. Car 5180, a 1917 Pullman product, sports ceiling headlining to cover the roof ribs.

While the reader may find these comments repetitious, mention must be made here that these grand old Low-V cars, alongside their earlier brethren performed yeoman service in hauling New York's commuters, shoppers, sports fans, theatergoers, students and in fact all types of people for nearly half a century. They, along with the old High-V's, owe nothing to anybody and paid for themselves and earned their keep over and over again. Happily a train of Low-V's has been preserved by the Transit Authority and has been run on excursions for several years, and New Yorkers can occasionally be reminded of the grand old IRT as it once was. The likes of such rugged, reliable equipment will never be seen again. Perhaps people like to see something new once in a while, and while to commuters and railroad men alike there is little room for nostalgia, one must look back in retrospect and compare performance of the system while those old relics were in service over 40 years, to the same system in the 1970's and 1980's with newer equipment which deteriorated much faster. One subway commuter quipped to a news reporter on the condition of the subways a few years ago, "The old cars looked and rode like Sherman tanks but at least they WORKED! " Amen to these words of wisdom.

Restored Low-V's await departure from Astoria, Queens on a fantrip. Although this was once an IRT line it is now served by the BMT. Note gap between car and platform; the IRT cars were narrower by a foot than BMT-IND cars. The concrete arch is part of the elevated line of the Amtrak route from Penn Station to New Rochelle. Franklin B. Roberts.

Section G: Steinways, Trailers, and Conversions

We have by now read about all the innovations of the Interborough on their rolling stock and the evolution of equipment from some of the earliest electric multiple unit cars built thru. the perfection of the art. There are a few side stories yet before we close the book on the IRT and some of them will be told here.

As a small footnote to the story of the Low-V's is the story of the Steinways. This class of car was specially powered for operation in the Steinway tunnel line which connected with elevated routes to Astoria, Corona and Flushing which were the IRT's only intrusion into Queens. The reader may think of Steinway pianos upon hearing the name, and of course the tunnel was named for William Steinway, the piano manufacturer with a plant in Long Island City. There is also a Queens street named for him. Back to the rails, however. The Steinway tunnel was built as a streetcar tunnel, a few years before the 1915 delivery of the first Steinway cars. Grades were 4.5% in this tunnel and conventional IRT equipment could not climb them, at least not with the combination of motor and trailer cars in their conventional trains.

The Steinway car was thus developed, which was a standard body IRT car, with different gear ratios for climbing those grades. Motors were less powerful than those in High-V, Low-V, or Flivver cars but as there were no trailers in trains of Steinways horsepower in a train was about equal. They never were exceptionally fast but were still able to make IRT running times when they were transferred to the Mainline, or Manhattan and Bronx routes in later years. Air brake on the Steinway Cars was schedule AMUE. They could be distinguished by a red line under the car numbers as they were identical in appearance to other types of cars.

A 6-car train of Steinways heads north between 166th and 169th St. stations on the 3rd Ave. line in 1959.

As we have already mentioned the Steinways were probably the first Low-Voltage cars delivered to the IRT, with the 12 car order from Pressed Steel Car Company in 1915. Along with the 1916 order of Low-V's from Pullman some 70 Steinways were delivered. In 1925 American Car and Foundry delivered 25 Steinway cars to the Interborough, and these were in fact the last standard body IRT cars built. Last Steinways placed in service were 30 cars converted from High-V and Low-V trailers built as part of the 1915 and 1916 orders from Pullman. The Steinways served the IRT Queens lines until 1950 when new R-15 cars replaced the last of the old equipment there. By now the only IRT operation in Queens was the Corona-Flushing line as the Astoria line was given over to sole BMT (Division of the city-owned system) operation.

Next home for the Steinways was on the Lexington-Pelham Bay local line, where they served along with the old High-V's until 1956 when the new R-17 cars bumped them from service. They were then spread over both IRT East Side and West Side routes where they were in service until the end of 1963, in quite limited numbers. A handful of them survived until early 1970, mixed in trains with 1938 World's Fair cars and Low-V trailers, on the 3rd Ave. Line in the Bronx.

Along with their huge fleet of motorized passenger cars the Interborough also had over 600 non-powered cars, or trailers in their subway fleet. Some mention has already been made of deliveries of trailers, and further information can be found in the roster. About all that is necessary to describe them will be done now. All IRT subway trailers were of standard body, steel construction and identical with motor cars in appearance except for lack of marker lights on the ends. As these cars had no control cabs they could not be operated at the head or rear end of trains and therefore needed no markers, so they looked a little more like standard railroad coaches than their motor counterparts. None of the trailers except 75 cars of the 1922 order had air compressors; the High-V trailers had no 3rd rail contact shoes as they received power for auxiliaries thru the bus jumpers from motor cars. All of the trailers were built by Pullman, in 1915, 1916, 1917 and 1922.

|

October 6, 1963: Steinway 4562 laid up on center track on the Jerome Ave. line. Note the (red) line under the number; this distinguished the car as a Steinway. In a few hours this train will be hauling the crowds, but the end is near for these venerable relics. Franklin B. Roberts. |

Low-V trailer 4857, at 46 years of age, in a train of World's Fair Cars on the 3rd Ave. line in the Bronx in 1963. This was a 1917 Pullman product. |

Makeup of a ten car train was seven motors and three trailers, while seven or eight car trains could have two trailer cars. Five car trains run on some locals and late night services had either one or two trailers and the fact that with three motors and two trailers a train could make schedule time was proof of the power of the old motor cars.

Mention has already been made that some trailers were converted to Steinway motors. In 1952 there was a conversion of 28 trailers to High-V motor cars but these never received controls, were run as "blind" motors in the trains and of course still looked like trailers. They had a red "M" over their number to identify them, and within six years of conversion were retired.

In addition to all of the cars described so far were two collection cars built nearly identical to the standard body cars but with no center doors and a bank-type barred window on each side for transfer of money collected into the car. Both were built by Pullman, 1915 and 1917, were trailers and had no controls.

In their last days of mainline service these old Steinways arrive northbound at 167th St. on the Jerome Ave. line, in 1963. Car 4562, a 1916 veteran, leads. Franklin B. Roberts.

Last home for the 1938 World's Fair cars was the 3rd Ave. line in the Bronx. A northbound train is shown stopping at Claremont Parkway station. A Low-V trailer was in the center of this typical consist.

Section H: The Last Cars Built For the Interborough

In 1938, on the eve of the 1939-40 New York World's Fair, the IRT decided to order 50 new all steel cars as showpieces for the World's Fair, to be run on the Flushing line to the site of the fair in Corona. They were entirely different in appearance from anything the IRT had owned up to this time, with no vestibules, doors located similarly to the BMT cars and a roof which departed from the railroad roof design of earlier IRT coaches. If they were more modern in appearance they were no advance mechanically as they were built to be compatible with Steinway cars built between 1915 and 1925. Modern features which the BMT and Independent systems had adopted, notably automatic air-electric car couplers which eliminated the manual labor and time consumption of cutting and adding cars. These still had couplers which had to be uncoupled by hand rather than compressed air, angle cocks, which had to be closed manually, rather than tappet valves which would automatically seal trainline air pipes when cuts were made, and jumper cables between cars rather than electric portion slides which would make up when couplers mated. Independent system and BMT cars could be "cut" or uncoupled in a matter of seconds, a cut on IRT stock took minutes, not to mention the heavy work for the men of removing jumpers from between cars, and "breaking locks" on the couplers manually. These 1938 cars even had oil lamps rather than electric at the ends of the train!

Not to be critical, however, it made sense for the IRT to have a car compatible with existing equipment, much as the Long Island Railroad had ordered cars in 1963 that were compatible with cars built in 1908! These cars were in all cases attractive, cheery, and comfortable for the passengers and were not a mistake nor poor planning.

All World's Fair cars were motors, with motorman's controls on one end of the car only, and conductors controls at the opposite end, probably an economy measure as the IRT was in bankruptcy at the time. These cars served the IRT Queens lines until 1950 when they were replaced, along with their Steinway cousins, and were sent to the Lexington-Pelham Bay local line. They were later to serve on other IRT lines and end their days in passenger service on the 3rd Ave. Line in 1970, when they were replaced there by some of the same 1949 era cars that crowded their turf in Queens in those days. Some of them wound up as work motors as did their older cousins.

They did not look much like the old IRT, and even though they were a small part of the fleet they were the last, but not least.

|

Looking much like standard railroad coaches, the old IRT subway cars had much more hardware. Pantograph gates were to keep people from being pushed to the tracks at stations; the boxes at the roof end were colored marker lights to show the train's routing. Door control boxes are also in evidence. This pose was of the ends of two Steinways at Gunhill Road on the 3rd Ave. line in 1963. |

World's Fair cars lead a southbound 3rd Ave. train near 200th St. in 1963. |

|

The only car in service in the last years of the old Interborough fleet to show the company name: Car 5677, a 1938 World's Fair car, poses on the 3rd Ave. el near 204th St. station. Franklin B. Roberts. |

Copyright 1985 by Edward C. Davis, Sr. Reproduced on nycsubway.org with permission. Webmaster's Note: The photos presented in these articles were in many cases scanned from the original slides obtained from the author. Where the original slides weren't available, scans from the book are used. In a few cases, similar photos from the collection of nycsubway.org were used instead of the low-quality scans from the book. These are all noted as such in the captions.

| ||||||